שעשוע רציני

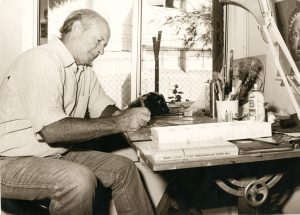

זוהי תמונה משפחתית כמעט אידילית: חיימה חיון עובד בעוד בנו הצעיר ישן בעגלה, ואשתו, האמנית והצלמת נינקה קלונדר, מתעדת את תהליך הציור במצלמתה. לקראת תערוכת היחיד שלו במוזיאון חרונינגר, המציינת את עשר השנים הראשונות שלו כמעצב/אמן, התמקמה המשפחה במחסן המוזיאון בחרונינגן לכמה ימים כדי לאפשר לאמן לצייר כמה ציורים גדולים על קנבס.

This article was written at 2014 by the exhibition cutaror, Sue-an van der Zijpp, before it openned for the first time at Groninger Museum, Holland.

It is an almost idyllic family scene: Jaime Hayon at work while his youngest son sleeps in the buggy and his wife, artist and photographer Nienke Klunder, records the drawing process with her camera. In preparation for his solo exhibition in the Groninger Museum, which marks the completion of his first ten years as a designer/artist, the family has installed itself in the museum depot in Groningen for a few days, allowing the artist the opportunity to make a few large-scale drawings on canvas. Apparently effortlessly and without any evident wavering or muddling, he draws elegant lines with thick felt pens on the huge canvases. His efficiency, precision and speed are astonishing, evoking associations with automatic drawing, a technique practised by the Surrealists. Indeed, his work clearly displays stylistic correspondences with this movement. Immersed in his work, with earphones over head, he produces a complete fantasy world in no time.

Now and again Jaime retreats from the drawing to create some distance. With infectious enthusiasm he reveals what it is all about: ‘It is a kind of genesis, a bit like the Egyptians represented their world of divinities. But here it concerns the way the cactuses and pigs came into being, and all the strange things that occurred in the process. It is a sort of titanic struggle for creativity and rockets are part of the battle; but this figure is locked in a happy embrace with that other one.’ And, indicating the finely drawn mechanisms in the joints: ‘They are machines of a kind. Do you notice that they are like puppets on a string?’ And who is pulling the strings, I ask. ‘Yes, that’s something I don’t explain’, he grins.

Drawings and their inherent narratives form the core of Jaime’s work. ‘Most of all, he would love to do this all the time’, Nienke confides. Jaime draws everywhere and continually, as is shown by the enormous stack of sketchbooks, some of which will also be on show in the exhibition. During one of the visits to his studio in Valencia, we browsed through these books. The earliest sketchbooks date from 1997 and resemble agendas or diaries in which every scrap of space has been occupied by glued-in photos of friends and all kinds of pictures and memorabilia, occasionally elaborated with his graffiti-like doodles. There is also a snapshot of a party at which pop celebrity Peter Gabriel is dancing with designer Philip Starck, and a business card of the then relatively unknown chef de cuisine Ferran Adrià. All kinds of images of cactuses and Michelin-like figures can also be discerned, elements that are later assigned a place in his first autonomous work. It is a cacophony of ideas, bizarre figures, jokes, stories and loose ends, events and fantasies. Subsequent sketchbooks have a larger format in which the drawings, now clearer and more elaborated, are grouped around a concrete project.

The fact that Jaime’s work might be important to the Groninger Museum was evident right from the first meeting in 2006. His creative talent, unparalleled drive and professional capacity to convert all this into a rapidly growing body of work, in which his personal universe is animated in all kinds of ways and in all kinds of media, formed an important reason to add his work to the museum collection. In addition, the recognizable signature, humour and narrative quality of the work were also major contributory factors. These are all features that stand in stark contrast to the principles of minimalism, functionalism and the modernist credo: form follows function. With this approach, Jaime assumes a distinctive position within his generation of designers – some of whose work has also been included in the museum collection and who all work at the interface of art and design. With his deployment of anthropomorphous forms, his outspoken use of colour and his dread of decoration, he is also akin to his Mediterranean neighbours: the Italian post-modernists who came to prominence in the eighties and who formed an important anchor point for the museum building and design collection.

Custom made versions of the Mediterranean Digital Baroque and Mon Cirque installations have now been included in the museum collection, and The Tournament was also recently acquired: a life-size chess set made of turned wood and ceramics, commissioned by the London Design Festival in 2009. During the festival week it formed the centrepiece on Trafalgar Square. At the time, Jaime had been living in London for more than 3 years and had made an in-depth study of British culture and the history of the city. He was directly inspired by the fact that the Battle of Trafalgar, the sea battle in which the British navy under Admiral Nelson fought against a Spanish-French alliance in 1805, had been ultimately won by the British (otherwise the square would have been named differently of course), although Nelson lost his life in the battle. In his work he processed various British icons such as towers and domes in London and subsequently painted these with all sorts of motifs and extra details, including a scene in which a king slips on a banana skin.

The ability not only to transform spaces into sections of his own universe, but also to transport visitors to various realms within this universe, was a key reason to ask Jaime to convert the museum library into a new Information Centre. In 2009, under his supervision, the unsightly museum space was transformed into a surprisingly light, attractive and almost fairytale environment that, with its many rounded shapes, paid cheerful homage to a sort of retro-futurism. Without books in view, but with a mini-theatre for screenings, an abundance of mirrors, roofed-over padded chairs, and a large marble table – also with roofing with built-in computers – visitors are invited to linger here and to absorb the information on offer. As is characteristic of all Jaime’s work, this interior, with its superior level of finishing and high-quality materials, is hyper-aesthetic without being intimidating or authoritarian. The visual language is much too amusing for that. Instead of evoking distant admiration, his work invites people to interact. It attempts to fire the imagination of the users so that they can imagine themselves different characters in a different world.

Jaime was educated as an industrial designer in Madrid and Paris. ‘But actually I was not so certain that I wanted to be a designer’, he remarks. ‘It was more a sort of excuse to express myself in this world, and because I had been educated as a designer, I did it that way. I was always busy with drawing, even when I worked with Fabrica, the design research centre of Benetton. It was a kind of utopian thinktank where I was head of the 3-D department. But ultimately I was too much of a manager and I just wanted to make things. So I simply began my own business.’ The breakthrough came in 2003, when Jaime was invited by the London gallery owner David Gill to hold a solo exhibition. The result was a ceramic installation with murals, called Digital Mediterranean Baroque. The work seems an explosion of bottled-up creativity. It is a kind of forest of ceramic cacti, populated by supersonic pigs and birds, an image that certainly reaches back to memories of a cactus park on Lanzarote. Many other influences are also recognizable, such as the skate-aesthetics and graffiti from his youth and Spanish art-historical elements that induce associations with Picasso and Miro. But MDB is also primarily about his fascination for ceramic material and its possibilities. With this exhibition, Jaime launched himself into the art world, apparently from out of the blue.

The design world of 2003 differed from the one for which Jaime had prepared himself during his study periods in Madrid and later Paris. Both schools were rather traditional in a modernistic sense: ‘There they were still discussing Bauhaus, Dieter Rams etcetera’, he recalls. From the end of the nineties onward, design had moved much closer to art, a development that nurtured all kinds of hybrid forms that were less oriented toward resolving practical problems. The ideal of the democratization of strictly functional and affordable common-or-garden modernism, as propagated by a series of exhibitions organized by the MoMA with the title Good Design or later exemplified by the Swedish furniture chain IKEA, seemed to have made way for designers who tended to focus on conceptualism, (dry) humour, lightheartedness, experiment, research, decoration or (personal) narrative.

In the last decade, the emphasis also increasingly shifted from accessibility toward progressively far-reaching exclusiveness, limited editions or even unica. Designers Ron Arad and Marc Newson, who produced expensive limited editions and exhibited their work in leading galleries and museums, blazed the trail for younger designers who stretched the boundaries between design and art even further.

This new design climate proved to offer the right breeding ground for Jaime, who rapidly developed into a super-productive allrounder. Within a short period he was working with many renowned producers and customers for whom he designed objects such as figurines, lamps, shoes, vases, furniture, bathrooms, interiors and a life-size chess set, in addition to his own autonomous work. Such creations earned him all kinds of prizes and honourable mentions worldwide. All this work was consistently presented by means of photographic campaigns, shot by Nienke, which showed the designer in various guises and which were particularly striking within the design world. For instance, she managed to persuade Jaime to dress in a pink rabbit suit, or in a padded suit with ‘spout’ ears, sitting on his green chicken-shaped rocking chair. The images not only betray a penchant for dressing up and fantasy settings, but also convey the idea that objects can have the same (emotional) transformative effect on the user as clothing has.

However, regardless of how deliberate and methodical his progress appears to have been, that is certainly not the case, says Jaime. ‘Often, one thing just led to another’, he remarks, summarizing his career. ‘MDB was not a typical design project, that only happened with Mon Cirque in 2005. That was about a kind of “fool’s aesthetic”, a kind of surrealistic world in which all sorts of mad things happen and in which objects can come to life: vases turn out to be creatures, the table, with its various legs, seems to dance, and flowers spring from horses’ heads on the wall. The craftsmanship is of primary importance here. For example, no moulds were used in the making, and it is all handcrafted. ‘But,’ he continues, ‘people from the design world, such as Ramon Ubeda or Oscar Tusquets, came to have a look and in this way particular aspects were picked up and that would lead to a project for bathrooms for instance.’ Some of these design elements returned in the Showtime collection that was launched at BD Barcelona in 2007.

Having detached himself from his traditional design education, and without the coercive ballast that a strong national design tradition can have, such as the sober modernism that was long dominant in the Netherlands, Jaime generated a style that is repeatedly described in words such as ‘baroque’, ‘eclectic’, ‘skate-style’, ‘surrealism’ etc. But it is not quite as straightforward as that. Jaime: ‘To me, it’s all about creating an own individual world and about improving things that already exist. Of course you can point to influences, but I am primarily myself. I take inspiration from objects for children, for example, such as toys – and even more so now I have children of my own. But I am also attracted to kitsch, nostalgic objects, forgotten corners, trashy alleyways, things that others often find ugly, bizarre or scary, in bad taste: I find them marvellous!’ He displays books with pictures of all kinds of folkloristic objects, various types of faces and miscellaneous kinds of junk. ‘Regardless of how ugly we often consider them to be, they are also things that are a part of our collective memory. I often see something, such as this, for instance,’ pointing at an image of a somewhat unfortunately modelled earthenware teapot in the form of a chicken, ‘and then I think: hey, I can do something with this.’

An important factor in his work is the ongoing dialogue he conducts with his partner, Dutch artist Nienke Klunder whom he met during their time at Fabrica in Italy. Recurring themes in Nienke’s work are identity and transformation, elements that are also explicitly covered in Jaime’s work and which are additionally accentuated in the photographic campaigns that Nienke creates. This was clearly manifest in the Showtime collection, with padded chairs on elegant legs. For this campaign, the designer was clothed in black, with dancing shoes and top hat like Fred Astaire. She also designed his first major book that was published in 2008. ‘My role is that of art director’, she says, half seriously, half joking.

The series entitled American Chateau was a joint project. It consists of photos and objects in which icons of American culture, such as hotdogs, doughnuts and big cars are presented in a lightly absurd manner. Nienke, who is also an American citizen as the result of her birth in the USA, has always been fascinated by excessive forms of abundance and extravagance, as viewed through European eyes. Photos show faceless female figures, some of whom have such enormous bosoms that they are supported by Dali-like stays so that they do not collapse. Further, there is also a table in the shape of a stretched limo, where the owner can use the ‘boot’ to store the cutlery, and a purple hotdog that is also equipped with a type of surrealistic support.

In addition to the concept of FUN – an apparently organically embedded imperative – his work is also characterized by a great love of and fascination for craft, material research and experiment. He can talk on this subject for hours: a visit to a mangrove, the number of types of marble, the countless tints of white that the stone may display, or the amazing professional expertise and technical dexterity of the skilled employees who work at companies such as Baccarat, Lladro, Bosa or Kutani Choemon. He regards every new project he takes on as a challenge to explore, expand and manipulate the boundaries of technique and the prevailing conventions of the company in question. His experience with these occasionally centuries-old companies has resulted in continuous accumulation of professional knowledge, as well as an enormous admiration for the applied arts. On the subject of his esteem for Baccarat, the French crystal company, he talks about one particular expert, a crystal cutter, the best in the business, who was specially recalled from retirement and with whom Jaime had the privilege of working. In mentioning this, the designer seems to reveal a growing missionary urge to refine and renew, with his input, the techniques and traditions that are now under threat of extinction, and thus make them relevant to the design discourse once more. ‘Injection moulding, plastics, rapid prototyping, voxels, robotica?’ Not for Jaime, at least, not yet.

In the past few years he has produced quite a number of chairs. Jaime: ‘All of a sudden furniture firms wanted to see me. To me, that was an opportunity to experiment with new materials and techniques.’ His collaboration with Fritz Hansen, the Danish firm that produced classic items such as The Swan and The Egg by Arne Jacobsen, was an interesting encounter between the beacon of cool North-European styled modernism and his flamboyant Mediterranean temperament. The Favn sofa from 2011 and the Ro chair that was issued two years later are comfortable pieces of furniture that have the names ‘Embrace’ and ‘Rest’ when translated. Ro is explicitly advertised as a fine, spacious chair in which you can comfortably sit with a child on your lap. Both examples are present in his studio. ‘It was very difficult to get the sofa up the stairs, and for the moment that is a very good reason not to change studios.’ While turning the chair upside down to show the underside, he remarks: ‘I learned so many new things at that company. For example, this chair is a supreme example of the craft of upholstery; they are masters in that profession.’

In a time in which unbridled economic prosperity seems to have vanished definitively, and new austerity is challenging us to take a fresh look at our relationship with the objects around us, Jaime offers a surprising perspective. His work stimulates the user to reflect on and re-evaluate the European decorative tradition that he is reviving with his design genius. On the basis of his hybrid working method, in which he moves smoothly between art and design, he also appeals to our inner wealth, our powers of imagination. But he never does so in a coercive or stringent way. Ultimately, it is all about fun, serious fun.